In the HOLE

Escaping Cop Fantasies in the Tactical FPS Genre

I’ve been playing alot of HOLE.

HOLE is a pretty simple and tightly scoped single player extraction shooter. The player is trying to earn money and other resources to upgrade their base, guns and stats. They do this by dropping into maps and grabbing loot either from the dead bodies of enemies (who spawn in increasing numbers and difficulties as times goes on), or by grabbing loot from boxes and fridges around the map. Escape the level via a hole-generating microwave and keep any loot you acquired. Die, and you lose essentially all of it.

HOLE is also a tactical FPS. Your gun will jam occasionally if it overheats, and reloading often involves some gun manipulation to ensure rounds are properly chambered. This combines with the very high lethality of weapons to result in the player approaching situations slowly and tactically, leaning around corners, hugging cover, and generally prioritizing defence over offence. This is aided by an almost Battle Royale touch to the game, where the enemies spawned in will belong to one of three factions. These enemy teams will not only get into firefights with one another (dropping the resources you want to extract with you) but are also looking for the same loot piles you are. Just like a Battle Royale, you switch constantly between truly open exploration and following the sounds of gunfire.

All of the above makes HOLE pretty fun (along with it being called HOLE, which just has great mouth / typing feel). But the reason I’m so into it isn’t purely because it’s just very good at what it does (which to be clear, it is). It’s also because, while I theoretically enjoy many games in the tactical FPS genre, the aesthetics and traditions they tend to mine from just… give me bad vibes.

These vibes are perhaps best represented by the contemporary pinnacle of the genre, Ready or Not, a sort of spiritual successor to the infamous Swat series. Following in that series' vein, you play a leader of a SWAT team dispatched to various high-danger situations, needing to kill or apprehend “bad guys” while rescuing civilians. It's worth noting that the ability to aprehend bad guys is an enticing addition to the systems of a traditional Tactical shooter, allowing for non-lethal options in a genre primarily concerned with shooting dudes in the face. But this is not how non-lethal options are utilized in Ready or Not.

While you can in theory be non-lethal, many enemies just won’t allow themselves to be captured, and because lethality is high, you also never want to drop your guard in case the guy you’re shouting at suddenly fires back. The ludic result is less that the non-lethal systems represent an end goal to be pursued, but rather a thing "good play" requires despite it revealing the player's position and losing them the tactical advantage. Most of the time, the result is the player and enemy briefly exchanging expletives at eachother around a corner, rasing the tension until it's ultimately broken by gunfire. You can, occasionally, actually handcuff a suspect by talking them down. You can even shoot someone non-lethally, allowing them to be handcuffed afterwards (though you will hear their pained screams for the rest of your time in the mission). But even this leaves you exposed, prone to being shot at by a hidden assailent. All of this comes together, alongside the other systems, to build tension, to create a certain “viscerality” and “rawness” that the framing of the game implies should be present. And it just feels icky to me.

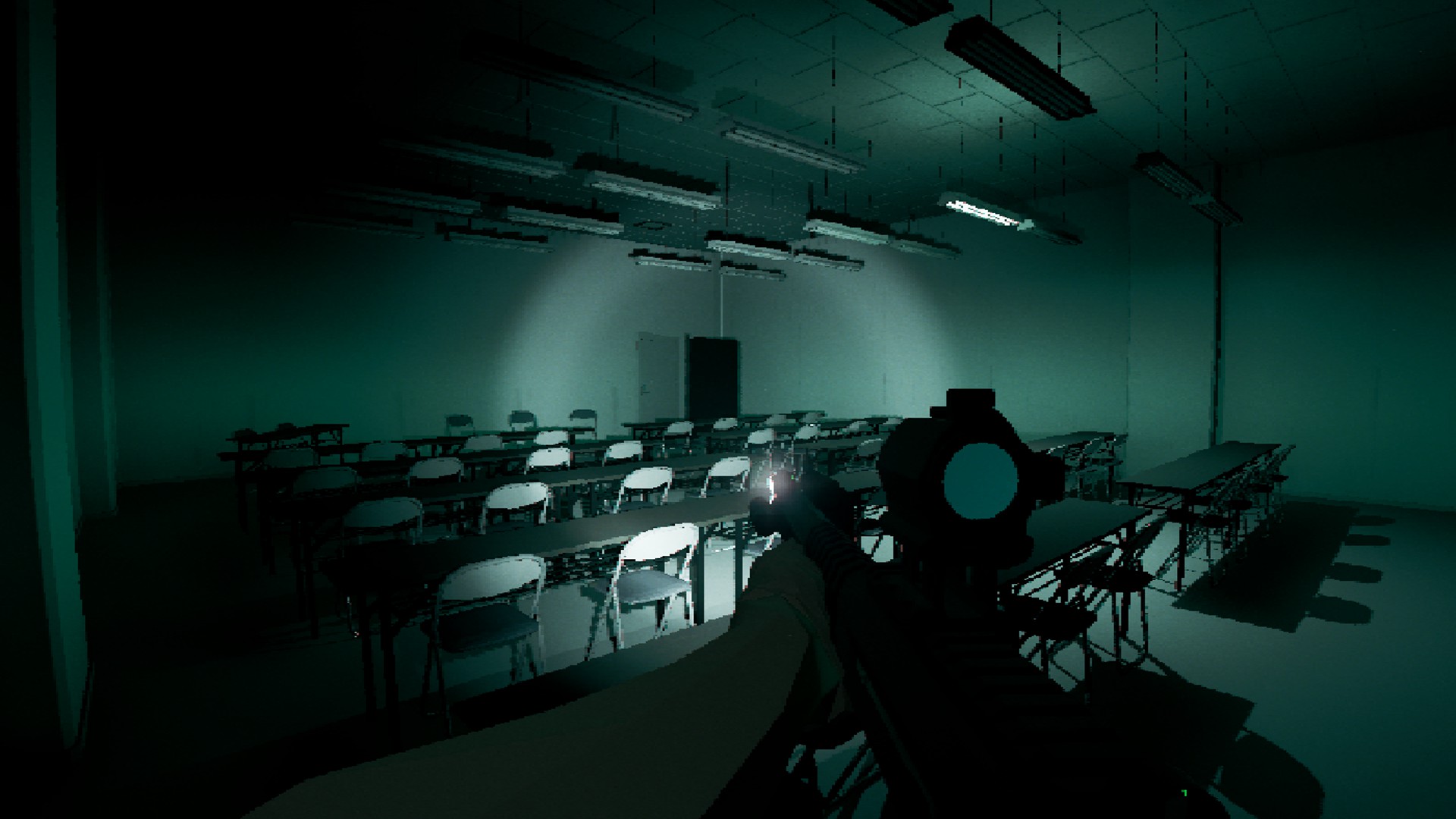

In fact, Ready or Not is such a good example of the Tactical FPS genre because of all the ways it leans into this icky excess. Graphically, textures and lighting models are not just meant to seem realistic, but further utilize low saturation, and dim lighting for a harsher, bleaker visual presentation. The audiowork reinforces this, not only with gunshots and door kicks that are unfathomably loud, but also in the way everyone is constantly talking, shouting, and / or swearing. There is an emphasis on the civilian, not just in the mechanical sense of civilians you need to rescue, but also in the sense that the world inhabits a certain view of “reality”, that again serves to heighten tension. This is perhaps no better represented then the game’s most contraversial map, Elephant, which takes place at a college during an active school shooting, complete with the enemy AI searching for and shooting students while you raid the building. Meanwhile, players get to unlock and outfit themselves in a variety of military hardware, with the awkward effect of making the team seem less like a unified government force and more like some sort of ragtag militia taking matters into their own hands. The end result is that the game is an almost idealistic militarized cop fantasy: A pure expression of the notion that not only is any location in the world always mere seconds away from devolving into a bullet strewn nightmare, but that those responding to the crisis must be given ultimate authority and power. They alone can solve it with big guns, loud voices and badass vibes.

This is not all to shit on Ready or Not. So much of what I’m discussing here could just as much apply to the fantasies of Call of Duty, Rainbow Six: Siege, Six Days in Fallujah, or any other number of shooters that integrate military or cop roleplay. In some ways I even commend Ready or Not's commitment to making these situations feel altogether horrific, unlike many of its peers. But more importantly, we do ourselves a disservice by outright denying the appeal of the fantasy at play here. Especially in a culture like the US, where the prevalence of gun culture, militaristic police forces and actual horrific scenarios like the ones depicted in Ready or Not (alongside the fearmongering and scapegoating around them drummed up by politicians and media), the notion of wanting to play out one of these scenarios, to try and understand how they might work, makes sense in the foundational ways that we understand play.

However, if these off-putting vibes and this, for lack of better term (I'm sure academics have a better one), "Reality play" are meant to help people work through complex emotions, then people LOVE working through complex emotions. The game has over 170,000 reviews, making it an incredibly successful game almost regardless of it's scale or budget. When looking for footage to reference for this piece, I was able to find multiple multi-million view youtube videos just specifically about the school shooter map, while a video promising “REAL Marines DESTROY the Hospital MAP on Ready or Not” has over 5 million views. Even if people are finding this game uncomfortable or horrific (which many comments, reviews and videos do seem to imply), they are also finding it fun. They find the fantasy it represents appealing to partake in, and even have a desire of seeing that fantasy not just translated into reality, affirmed by the same people who perpetuate the fantasy in the first place.

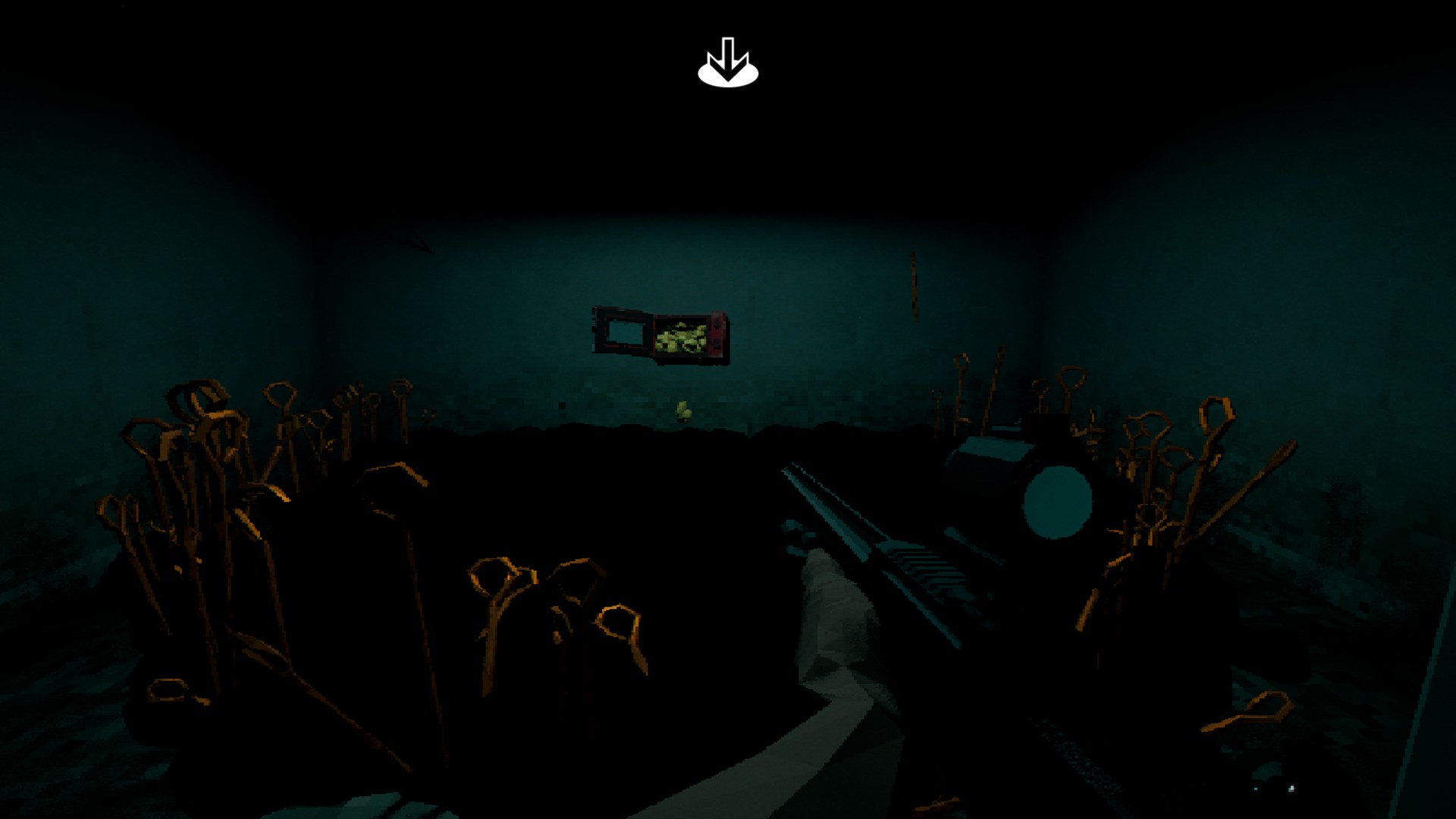

HOLE does not represent a fantasy, nor does it really bear really any resemblance to reality outside of the complicated and lethal nature of firearms and the universal notions of “gravity”, “infrastructure”, "money" and “humans”. The levels you run through are abstract, endless and inescapable, taking the form of offices, sewers and apartment complexes that are completely devoid of any sense of lived reality. A pixelated filter covers the screen, which combines with the goofy, almost infantile masks your enemies wear, the animal crossing-like speech they employ, and the classically video-game-y “Ting!” of picking up money to make the whole thing feel entirely separate from our lived reality. That is to say that, despite it’s many mechanical similarities and even connected lineage to games like Ready or Not, at no point does it feel like an active shooter situation. Rather, HOLE employs the exact opposite approach of Ready or Not, a sort of hyper-unreality, that allows players to focus on the fun of the game’s mechanics and internal logic, without needing it to be connected to contexts or fantasies found in the outside world.

This isn’t to say that HOLE doesn’t engage in politics nor fantasies, but rather those elements are focused on its own internal logic and context. It wants you to think about money, and what people are willing to do for it. It also wants you to think about guns, what they are capable of and used for. And the fantasy being presented is that you get so good with guns that you can kill everyone, and have essentially infinite money. But your “home-base” is just an isolated section of sewer, and the only thing you can spend money on is gun attachments and things to shoot at. What any of it is meant to be about, in the loosest of terms, is oblique. What any given player pulls out of HOLE is thus far more likely to result in something far more personal and frankly interesting than if the game were connected to a much firmer reality or fantasy. But perhaps even more more important is that I just don’t feel actively uncomfortable when engaging with it.

The Tactical FPS genre presents fun and interesting mechanics that heighten tension and provide a compelling framework with which to interact with the world (in many ways connected to my piece on Stalker 2’s spatial intimacy, as that game also has tactical FPS elements). By having weapons of hyper lethality that need to be treated very carefully, alongside having active and unpredictable dangers put against you, the one thing that becomes both your most reliable aid and greatest obstacle is space. Do you know where you are, where the enemy is, how to flank them and how they could flank you? Corners become spaces of heightened fear and then relief, hallways are a ramp of tension, and junctions are just a no man’s land that you can only pray someone else walks into before you. It’s this need to understand how multiple systems interact with space that make me so enamoured by the notion of the Tactical FPS. But due to the nature of play, they often manifest as power fantasies. Due to modern traditions of the FPS genre, they are nearly always cop or military fantasies. Combine that with some progression systems and a gritty edge, and the whole thing turns into hyper-militaristic, almost fascistic roleplay. My fun, interesting space play is still there, but it's surrounded by such a despicable crust that I just can't imagine “having fun” without also feeling deeply gross about the whole thing.

But it’s important we remember, not just about this genre but any genre, that there are ways of harnessing the fun or compelling elements in a thing we enjoy without necessitating that despicable crust. Traditional immersive sims, while also prone to violence, can produce the same sorts of careful understanding of space and utilization of player tools and systems that any tactical FPS does. Moreover, in being able to remove themselves from the cop / military fantasy, they are also able to provide more interesting objectives than just “kill all the baddies”, more interesting tools than just “gun and handcuffs”, and structurally they are far better equipped to represent the results of the player’s actions or question player choices. On a completely separate track, and while I didn’t make the connection until writing this piece, I do think The Crush House (a game I worked on previously) actually takes on many of the aspects of the Tactical shooter (careful positioning and sightline management, awareness of NPC pathing and behaviour), but via placing them in an entirely different context (using a camera to film contestants on a reality TV show), The Crush House is able to use that same gameplay input to explore entirely different kinds of fantasies and contexts.

Yet HOLE is the kind of game, and game design, that I also really love to see. HOLE is undeniably straightforward in its adaptation of the Tactical FPS genre, but is in no way subservient to it’s aesthetics or traditions. And this is important, not just for maintaining the core of a genre, but also for enticing players away from other, more harmful fantasies. I would love a world in which we had just way less games about guns or violence in favour of other mechanical interfaces, but we can’t ignore, not resent, the public for desiring this kind of work. But it’s then just as important that we internalize that we don't need to give an audience exactly what they want. We can filter, refine or challenge their desires, even while maintaining the exact kinds of genre, mechanical and even narrative aspects they came for. And that needn't always be an exercise in discomfort or direct opposition to the player fantasy. Sometimes, it's just as worthwhile to be like HOLE, and have a little fun with it.