Touching the Bounds

Where authorial intent meets player anxieties

Imagine you’ve been playing a game for a few hours and, via machinations of the plot, you have been dumped into the center of a classically styled hedge maze. The game’s central antagonist taunts you from over loudspeakers, specifically noting how they were able to trap you in the maze, how devious the maze is, and how unlikely (though not impossible) it will be for you to escape the maze. As you explore, your player character comments on your current progress through the maze, including any moments where you arrive at dead ends or retrace your previous steps.

As you wander the maze, you feel Lost. Is it an enjoyable feeling?

Compare this to another scenario:

Compare this to another scenario:

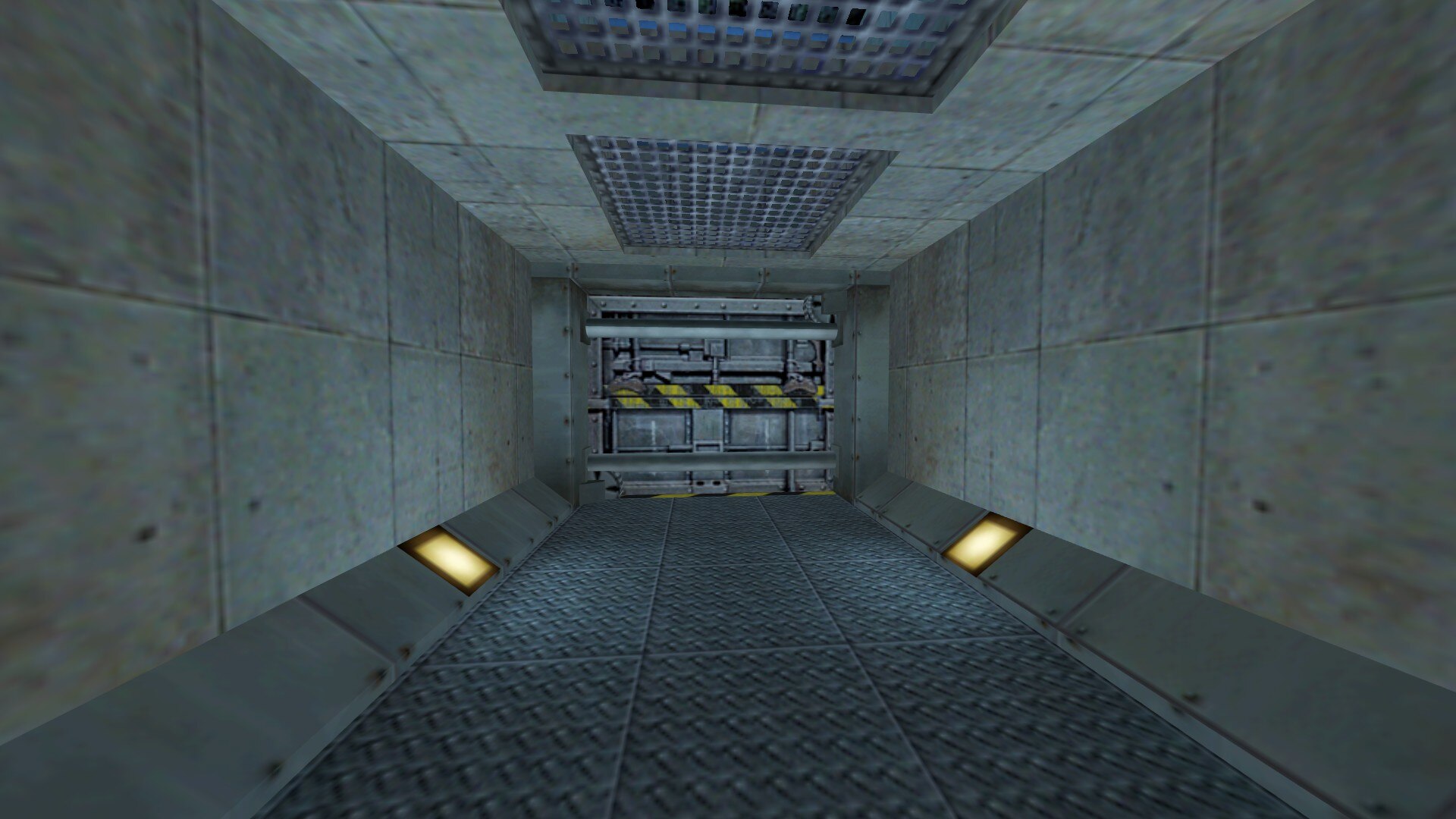

You’ve been playing a game for about 30 minutes, not yet having fully internalized the flow of the game, and you arrive into a sort of hallway space with doors at either end, with various bits of machinery dotted along the walls. As you move to the opposite door, you realize it’s shut. You go back to the door you entered through, only to realize it’s also shut. You start looking around the room, trying to identify if any of the machinery is interactable. Everything you try produces no results, nor provides meaningful feedback of any kind.

As you wander the room, you feel Lost. Is it an enjoyable feeling?

Most important to me is this: Which scenario would provide a more enjoyable feeling of being lost, and why?

Let’s ignore that this hypothetical is ultimately poorly constructed, and that I don't have the resources available to make both games just to test my theory. Instead, lets just analyze what we can hope the answers to these questions will have been, and extract meaning from them.

In the “Maze” scenario, while a player may feel lost, that player is also constantly given feedback informing them that they are meant to feel lost, and that any given scenario they go down was anticipated by the developer (because otherwise there would not be accompanying voice lines). The player thus doesn’t feel any anxiety in that experience of “being lost”, as they can tell that feeling is in line with the feeling they were intended to have in this specific scenario.

This stands in opposition to the “Room” scenario, where due to a lack of clear signalling and feedback, the player cannot tell if they are meant to feel lost. This in turn creates an anxiety about that “lost” feeling, as the player is not sure whether they "should" be feeling lost or not. Not only can they not escape this room and feel lost via the process of trying to escape, but so too are they also trapped in this anxious feeling.

From this hypothetical (and it’s hypothetical answers) we can extract three core ideas:

-

A game, whether consciously implemented by its developers or not, cannot only intend for how a game is meant to be played, but how a player should feel while playing. We’ll call the combination of these two notions the “Intended Play Experience”.

-

While a player might not particularly care about the intended play experience during the majority or even all of their play, they might stil have a desire to understand or simply “check in” on the intended play experience. We’ll call this “Intention Checking”.

-

As a result, beyond just setting up the dynamics that result in the player inhabiting the intended play experience, developers may want to provide active signals to the player that communicate what the intended play experience is at any given time. We’ll call this “Intention Signalling”.

Here’s a concrete example of this all in action:

While playing Baby Steps with my partner, we saw a castle in the far distance, specifically off to the right in a new area we had just entered. However, the path leading us into the area banked to the left, with it leading towards a bright light in the distance that marked the next checkpoint. This contrasted heavily with the lack of path to the right, which was instead made up of dense trees and foliage that quickly obscured any sight of the castle.

In many ways, walking to the left seemed like the Intended Play Experience (i.e enter the zone through the expected means, branch off and explore later once the path opens up), and as such we became uncertain about whether we should even try walking to the right. We wern't just concerned that we would hit an impassable obstacle to the right, and then need to backtrack, but perhaps more importantly that even if we did find a route to the castle by going to the right, we might miss out on a more interesting, richly detailed and deliberately designed path that would have appeared later on had we gone down the left path.

At this moment, we found ourselves Intention Checking the game, trying to see if this rightward path was an intended route. We ultimately decided to walk out just past the foliage to the right to see if anything laid beyond, and we were surprised to find a flat, uncovered ridgeline, easy to walk along, with a new path visible in the distance that seemed to head towards the castle. By providing these affordances and details, the game was not just communicating that going in this direction was viable, but went further to imply that that path was one considered and intentionally crafted by the developers for us to take. It did this via the process of Intention Signalling (or, we could say, by providing intention signals).

The question this entire scenario most arouses in myself is: “Why get anxious about how a game designer desired you to play their game?”. Once we’ve been given a game, it is in many ways our role as player to follow our own desires, and as such only interfacing directly with the intentions of the developer when they clash against our own. If we are in touch with this conceptual ideal of our role as a player, doesn’t trying to check how the designers want us to play stand in direct opposition to our ideals?

While I hold this counter-argument to be important, the unfortunate reality is that this “conceptual ideal of play” is, by necessity, ignorant of the lived realities of play. Put simply, while we can play any game in any way we want, that doesn’t mean that all those modes or styles of play are equally good, regardless of how "good" is defined.

On PC, I’ve put 90+ hours into Fallout 76, most of them from the height of the pandemic, but with a couple dozen hours spent in the years after. I’ve spent many of those hours simply roaming its virtual landscape, exploring points of interest and completing the occasional quest. My fondest memories of the game stem from a full 10+ hours of play, stretched over a couple weeks, where my home base was perched on a cliff on the outskirts of Morgantown. I hiked up and down said cliff dozens of times, often moving at a snail's pace due to being weighed down by loot and hunger / thirst status afflictions, as I explored the post-apocalyptic university town and the various small environmental stories within. Yet, even as I had these genuinely enjoyable and fulfilling play experiences, I also found myself googling a question multiple times: “How do I play Fallout 76?”.

To be clear, I knew mechanically how to play Fallout 76. You shoot and you loot and you build up a base while exploring and completing quests, and there was no part of the basic control scheme or interaction space that didn't make sense to me. I also can not overstate that I very much enjoyed my style of playing Fallout 76; this was not the case of me being otherwise unsatisfied with my playtime and thus trying to find ways to squeeze more out of it.

I just got the sense I was playing the game “wrong”: I completed quests only occasionally, ignoring the main quests entirely while also largely not engaging with the NPC filled towns. I mostly ignored all live events and co-op missions; I did try them a few times, but the gear and resources required immediately outmatched what I usually had, and the missions themselves didn't seem compelling enough to dedicate preparation time for. I also just leveled up very slowly: My 10 hours in Morgantown raised me only approximately 10 levels from 20 - 30, yet I was constantly surrounded by players who were level 300 or 500 who clearly weren't needing to put in that kind of hour count to keep their number ticking up (though nor were they generally participating in the kind of slow, methodical exploration I was engaging in). All of this together implied I was doing something wrong: that the game loop I partook in, while perfectly enjoyable, wasn’t the actual gameloop I was meant to be engaging with.

To be honest, I get this feeling all the time, often from live service games like Fallout 76, Destiny or No Man's Sky, ones that appear to have a specific loop of engagement that game systems are built around. Yet I also get it from Turn Based Combat games like Baldur’s Gate 3 or Final Fantasy X, where my best efforts to engage with those systems still often lead to difficult, slow or awkward encounters. Both styles of games, and many other examples, are ones I can have fun with, yet have an undeniable friction that I must push through. And that friction stems from a feeling.

The feeling is that, for whatever fun I am having or progress I am making, my play is still fundamentally misaligned with at least some part of the intended play experience. Exterior to my play, I'll find myself talking to friends, reading walkthroughs, scouring forums, watching let's plays and otherwise frantically googling, and all this in an attempt to find the signals that will allow me to understand how the game wants to be played. And in lieu of that understanding, I am left with this nagging anxiety that my play experience is exterior to the designer’s intentions, feeling lost in that experience of play. And I do not enjoy that feeling.

Am I saying that, if these games were better at intention signalling, I would have a much better time with them? Well, yes! It doesn't necessarily mean I would find the ways they want me to play them fun, nor does it mean I would simply inhabit their intended play experience. In fact, when confronted with these games intended play experiences, I might end up pulling back from the games, deciding that ultimately the entire game is aimed in a way I care not for.

But, I would no longer have that anxiety that I was simply missing some core aspect or notion of play. Maybe I'd actually really love these games intended play experiences and onboard them fully. More likely but still great, I could modulate my own mode of play with occasional dips into the intended play experience, thus experiencing the fullness of the game while holding onto my own play identity. However I respond to the intended play experience, there are countless examples in my play, and likely yours, where it would be comforting to reach out and grab it, to know how our own experience contrast againt what the designers intended. And thus, as a designer, I think it's worth considering how we design games to allow for that communication to be had.

It's worth saying that this theory ties into or alligns with many, many others areas of study / scholarship, most notably to me the Lusory Attitude, the Magic Circle, Death of the Author and just the general field of Semiotics, but probably many, many others that I am blanking on right now or am otherwise unaware of. It's also very possible that this lens through which to think about games has already been written about extensively under different verbiage, in which case, please let me know as I'd love to read it!

Regardless, this is a theory I'm increasingly applying to my own work, as a means through which to anticipate, direct and respond to player expectations and concerns. There is certainly more to say on how we signal our intentions to players, why players develop this anxiety in the first place, and how we ensure our intended play experience alligns with the player to hopefully elimate that need for intention checking entirely. But tbh this has been sitting in my drafts for over a month and was way too wordy already, so I'm going to happily leave it here for now.